Contents

This article focuses on the early development of blues and its emergence as popular music in the 1910s. For a general overview that follows the evolution of blues music from its origins through its contemporary forms, see Blues: About the Genre.

Overview

Southern African Americans developed blues music in the decades that followed the end of slavery. It incorporated elements of West African music that they retained during their American experience. While emancipation meant new freedoms for African American people, it also brought challenges, hardships, isolation, and sorrow. Blues emerged as an embodiment of and response to these unique circumstances. Personal statements by individuals superseded the communal music that was dominant during slavery.

In the 1910s, blues became a sensation throughout the United States. The blues that emerged as popular music built on earlier folk forms, but it was new and different. Professional songwriters and musicians composed and performed the music, and it reflected up-to-date trends in theater and vaudeville. It also revealed the symbiotic relationship between blues and another burgeoning form of American music: jazz.

Musical Roots

Rhythmic, melodic, and stylistic characteristics of blues are evident in the music of plantation workers of the antebellum South. They retained these practices from West African musical traditions, where song accompanied everyday activities of work, worship, courtship, and leisure. The many languages and customs Africans brought to the New World coalesced over generations into relatively cohesive bodies of African American music and culture.

African music is notable, and distinct from European music, for its rhythmic complexity and diversity. African drumming features polyrhythms, in which musicians play two or more rhythms simultaneously. Drumming was strictly limited or outlawed in America by white governments and overseers who were fearful of the potential use of drums to communicate and coordinate slave revolts. In the absence of drums, enslaved African Americans created complex rhythms through singing, hand-clapping, foot-stomping, as well as instrumental techniques used in playing banjo, fiddle, bones, spoons, piano, and other instruments. Rhythmic inventiveness is central to blues and other African American musical forms, including ragtime, jazz, gospel, rhythm and blues, and hip hop.

Blues music employs a range of melodic practices from West Africa. These include melodies that build on a five-note pentatonic “blues scale.” The flatted 3rd and 7th pitches of these scales are commonly called “blue notes.” Europeans and Euro-Americans often describe songs built on these scales as having a mournful sound. African and African American singers and instrumentalists slide, glide, and quiver between pitches. These techniques produce microtones and effects that standard musical notation is insufficient to represent.

Blues Scale

Field hands working long hours in the sun sometimes let out a long, musical moan, known as a shout or holler. A visitor to a plantation in the South described a holler in his observation of a man who “raised such a sound as I never heard before: a long, loud, musical shout, rising and falling and breaking into falsetto.” Field hollers could be wordless, or they might include improvised phrases and pieces of existing songs. Sharecroppers and laborers on prison chain gangs, railroads, and levees continued this practice after the end of slavery.

Alan Lomax recorded this example of a holler by Walter “Tangle Eye” Jackson at Mississippi State Penitentiary (1947).

The slow time and mournful nature of the hollers bear a close resemblance to blues, though blues songs are more structured. Their distinctive vocal textures are evident in the style of many blues singers, including Blind Lemon Jefferson, Skip James, Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Tommy Johnson.

Blind Lemon Jefferson “Black Snake Moan” (1926)

In West Africa, people sang group work songs as they carried out jobs and tasks. The singing often incorporated call and response, a technique in which a leader sings or chants a line, and the group echoes or answers it with a reply. African Americans continued singing call and response work songs on American plantations and other group work environments, including railroad and levee building. In blues music, call and response often occurs between a singer and a musical instrument.

Call and response is evident between Robert Johnson's vocal and guitar in "Cross Road Blues" (1936).

Through spirituals, enslaved African Americans applied call and response and other West African musical practices to Christian hymn singing. Both spirituals and blues often convey feelings of struggle or sorrow. While spirituals find solace in God and the promise of salvation, blues songs remain focused on the earthly realm. The practice of creating spirituals and blues includes drawing upon phrases or verses that are common to multiple songs. Spirituals are generally sung as a community, whereas blues is the expression of an individual.

The Development of Blues in the Postwar South

There is no precise moment when blues music was born. It resulted from the intermingling of many social factors and musical precursors. Abolition and emancipation offered three things that were essential to the development of blues: mobility, time alone to ponder, and the freedom to express grievances. Emancipation brought new hope for African American people in the South. Reconstruction governments offered political power, access to public schools, and jobs building railroads and roads. However, it was a highly contentious time, as Southern whites did everything they could to preserve the power structure from which they had benefited for centuries.

The withdrawal of federal troops from the South in 1877 marked the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of white Redemption. White Southerners severely limited African Americans’ abilities to participate in the political process through discriminatory voting laws and terror organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan, the White League, and the Pale Faces. The promise that African Americans might farm their own land was supplanted by a system of sharecropping and tenant farming, which kept them beholden to white landowners and in constant debt. Forced into segregated “separate but equal” public accommodations, African Americans were more isolated from mainstream American society than they had been under slavery.

Many African American men traveled from town to town in search of employment. Others wandered due to restlessness. Traveling on foot, horseback, or train, they exercised their new freedom to do what was denied them for so long. Among them were black musicians. Some were professionals, and others were plantation workers who made extra money playing for tips on street corners. These songsters, or musicianers, played a wide variety of music, including fiddle tunes, minstrel songs, spirituals, and narrative ballads. Black and white musicians freely borrowed songs and musical ideas from each other, resulting in a shared common stock repertoire. This gestation period birthed forms of American music that would take the national stage in the first decades of the twentieth century, including blues and country.

African American musicians played fiddle, banjo, mandolin, quills, pianos, and increasingly in the 1890s, the guitar. Guitars had been in the Americas since the earliest Spanish settlement of St. Augustine, Florida, in the late sixteenth century. Their popularity increased dramatically during the 1890s when companies, including Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward, started making inexpensive models available by mail order.

Black musicians gradually created new types of songs that differed from the interracial common stock. Blues ballads were similar in structure to the narrative ballads that British colonists brought to the New World, but they told stories relevant to contemporary African American life. They also employed the West African-derived vocal, rhythmic, and melodic devices that would become common to blues. Blues ballads include “John Henry,” “Frankie and Albert,” and “Stackolee.” Another type of song, the jump-up, strung together common phrases and verses, often unrelated, over simple guitar accompaniment of one or two chords.

Mississippi John Hurt: "Frankie" (1928)

Regional songs and styles emerged, though traveling musicians picked up and spread influences throughout the South. In addition to the lone songsters, troupes of performers toured professionally in minstrel shows and circuses, as well as smaller medicine shows. White performers in blackface makeup dominated minstrelsy, but an increasing number of black minstrel troupes, also in blackface, toured after the Civil War. Though minstrelsy reinforced negative racial stereotypes, it offered professional performance opportunities for African American entertainers in an era of limited options.

Blues as Popular Music in the 1910s

The term “blues” as a description for melancholia is rooted in the “blue devils” of sixteenth-century British literature. Blue devils were evil spirits thought to cause depression. As the term for a type of music, blues probably came into use around the turn of the twentieth century. Among the earliest references were in New Orleans, where it indicated a slow, sexy dance rhythm. Blues and early jazz were inextricably linked as they developed concurrently late in the nineteenth century. Black brass bands in New Orleans played blues-inflected jazz music on European marching band instruments, including the clarinet, trumpet, trombone, and tuba. In 1908, New Orleans produced the first published blues composition - "I Got the Blues," written by an Italian American named Antonio Maggio.

Blues became widely-known in the 1910s when it emerged as a modern trend in popular music. Two of the primary figures responsible for popularizing it are William Christopher “W.C.” Handy and Gertrude “Ma” Rainey. They were both professional entertainers who adapted music they heard in informal settings to the performance stage and published compositions. Handy and Rainey were creating something new and different from the folk forms they heard.

Ma Rainey may be the first singer to gain success as a blues specialist. She began performing as a teenager in the first decade of the twentieth century. With her husband, William “Pa” Rainey, they appeared in vaudeville theaters, circuses, and tent shows throughout the southeastern United States.

Ma Rainey: "Black Bottom" (1927)

Ma Rainey told folklorist John W. Work about encountering blues music for the first time in a small town in Missouri in 1902. As Work told her story:

A girl from town... came to the tent one morning and began to sing about the man who had left her. The song was so strange and poignant that it attracted much attention. Ma Rainey became so interested that she learned the song from the visitor and used it soon afterwards in her act as an encore. The song elicited such a response from the audience that it won a special place in her act. Many times she was asked what kind of song it was, and one day she replied, in a moment of inspiration, "It's the blues...". She added that the blues were not so named then, and that she frequently heard similar songs in her travels.

Gradually, blues songs gained more and more prominence in Rainey’s repertoire. In 1914, after several years with the Rabbit’s Foot Minstrels, Ma and Pa Rainey performed with a traveling circus, billing themselves as “Rainey and Rainey, Assassinators of the Blues.” Ma Rainey was also billed as “Mother of the Blues,” a recognition that has persisted to this day.

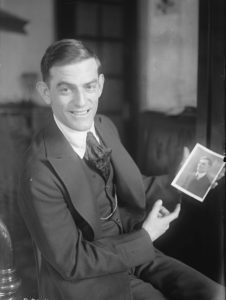

W.C. Handy was an African American bandleader, songwriter, and music teacher who became known as “Father of the Blues” for his role in making blues a popular music sensation. Starting in the mid-1890s, he toured extensively as a professional entertainer, singing with minstrel troupes, playing cornet and trumpet, leading choruses, and directing black dance bands.

Handy picked up musical ideas and styles from the locales he visited. He told the following story about a song he heard at a train station in the Delta hamlet of Tutwiler, Mississippi, in 1903. He had fallen asleep while waiting for a train and awoke to hear music.

A lean, loose-jointed negro had commenced plunking a guitar beside me while I slept. His clothes were rags; his feet peeped out of his shoes. His face had on it some of the sadness of the ages. As he played, he pressed a knife on the strings of the guitar in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars. The effect was unforgettable. His song, too, struck me instantly. ‘Goin' where the Southern cross' the Dog.’ The singer repeated the line three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with the weirdest music I had ever heard.

Neither the singer in Handy’s story, nor in Rainey’s, identified the music they were singing as blues.

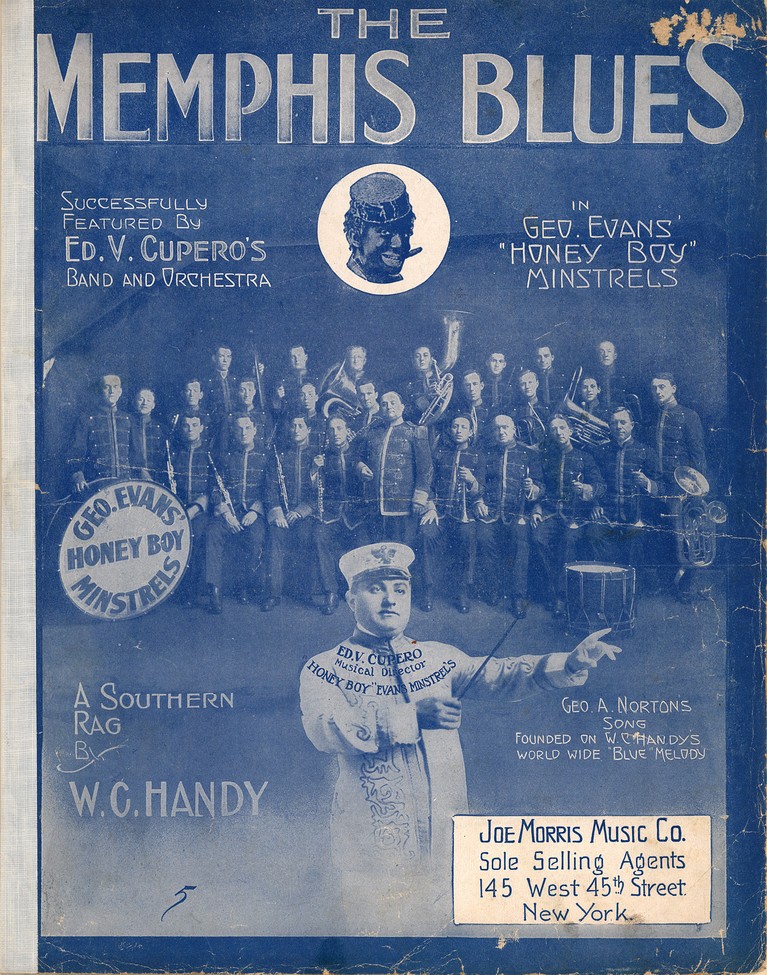

Handy was living in Memphis, Tennessee in 1912 when he published the sheet music for his composition “The Memphis Blues.” It was one of the first published blues songs, and sales of the sheet music soared. Dance bands across America played it because dance instructors paired it with a hot new step called the foxtrot.

Victor Recording Company’s house band, Victor Military Band, made the first recording of “The Memphis Blues,” an instrumental, in 1914. Morton Harvey’s recording of the song in 1915 was the first blues sung on record.

Morton Harvey: "The Memphis Blues" (1915)

“The Memphis Blues” started a national craze for blues music. Handy published his next blues, “The Saint Louis Blues,” in 1914. It was even more successful than “The Memphis Blues,” and it carried blues music around the world. “The Saint Louis Blues,” or “St. Louis Blues,” has since become a standard. Countless artists have performed and recorded it, including Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong, Bing Crosby, Glenn Miller, and the Boston Pops Orchestra. Handy's original composition, as well as several of his other pieces, includes a section with a habanera rhythm. This Spanish rhythm was popular in Cuba in the nineteenth century. It became integrated into the African American music of New Orleans, as musicians regularly ferried between the city and Havana. The first recording of "The Saint Louis Blues," by Prince's Orchestra, the house band at Columbia Records, includes this habanera section.

Prince's Orchestra: "St. Louis Blues" (1915)

"The Saint Louis Blues" was written with a chord structure that became very common in blues music. The twelve-bar form indicates a specific relationship among chords that are played across twelve measures (or bars) and repeat throughout a song. The form may have evolved from a shorter eight-bar form or from a longer pattern. In the example below, listen specifically to the chord changes that occur in bars 5, 7, 9, 10, and 11.

Twelve-Bar Blues Form

"The Saint Louis Blues" also features a lyric pattern that is frequently employed in twelve-bar blues songs. A single line is repeated, followed by a rhyming third line.

I hate to see the evening sun go down

I hate to see the evening sun go down

It makes me think I'm on my last go 'round

Bessie Smith, with Louis Armstrong: "The Saint Louis Blues" (1925)

The success of Handy's compositions prompted other composers to jump on the blues bandwagon, and the music grew in popularity throughout the decade. The sheet music for “The Memphis Blues” indicated that it was “A Southern Rag,” referring to ragtime music, which had been very popular since the mid-1890s. Many compositions included both words blues and ragtime, or rag, in the title or description. The genres shared many musical qualities, including the use of rhythmic syncopation, but blues was on the rise in the 1910s while ragtime was in decline. Both were essential ingredients in jazz. “Livery Stable Blues,” recorded by the Original Dixieland Jass Band in 1917, is widely regarded as the first jazz recording to be released commercially. The song is in the twelve-bar form.

Original Dixieland Jass Band: "Livery Stable Blues" (1917)

Although rooted in African American folk forms, white, professional songwriters wrote most of the published blues compositions of the 1910s. All the blues recordings of this period were performed by white vaudeville singers and dance orchestras with varied repertoires. Notable artists include Al Bernard, Marion Harris, and Marie Cahill.

Al Bernard: "Hesitation Blues" (1919)

While African Americans had been singing on sound recordings since the start of the recording industry in 1890, they mainly performed self-deprecating “coon songs” (see Ragtime: About the Genre) and minstrel show material. The music industry marketed and sold records and sheet music primarily to mainstream, middle-class, white consumers. They did not view African Americans as potential customers, so they marketed records by black artists to white audiences. Minstrel and coon songs performed by black singers sold to white record buyers because the material supported the dominant racial stereotypes and did not threaten the prevailing power structure.

In 1920, Okeh Records released the first blues recording by an African American singer. It launched black performers to new levels of success, finally singing music that was their own.

See Blues Queens and Race Records in the 1920s for more.

Playlists

Several of the songs referenced in this article are not available from Apple Music.

Apple Music

Spotify

YouTube

Further Reading

Crawford, Richard. America’s Musical Life: A History. W. W. Norton & Company, 2005.

Gioia, Ted. Delta Blues: The Life and Times of the Mississippi Masters Who Revolutionized American Music, 2009.

Jones, Leroi. Blues People: Negro Music in White America. New York: Harper Perennial, 1999.

Miller, Karl Hagstrom. Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

Milward, John. Crossroads: How the Blues Shaped Rock ’n’ Roll. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2013.

Palmer, Robert. Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta. New York: Penguin Books, 1982.

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History. W. W. Norton & Company, 1997.

Wald, Elijah. Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues. New York: Amistad, 2004.

Wald, Elijah. The Blues: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.